The Naughty and Playful Future of Iran

At war with Sufi mysticism

When Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, Supreme Leader of Iran, was a child no more than five or six years old, his father introduced him to Sufi poetry. His father read from the Persian poets Attar and Sanai Ghaznavi, the 12th century Sufi poets from modern-day Afghanistan, the latter of which is known for his Persian mystical epics that are only read in the most niche of graduate school programs these days. Sanai’s epic is the Hadiqat al Haqiqa, a book of ten thousand verses committed to the praise of Allah, to the praise of love and intellect and intimacy. The pages themselves are works of art, complex ornamental designs where the Persian language verse is inscribed into the form of flowers and birds, where gold leaf tapestries filled the margins with florid realms, like kaleidoscopic dreamscapes that made worship of this strange prose. Khamenei took to the verse almost immediately. He began writing much of his own nubile minded verse. You can find them in online archives if you are diligent enough. They read much like an sixteen-year-old’s overly eager poems, like someone who had just been introduced to Rimbaud and was doing their best impression. But the little Ayatollah was only five. In other words, he showed incredible promise, and his father knew this and instructed his son to keep practicing. He introduced him to the other ancient Sufi poet Farid ud-Din Attar of Nishapur. Attar’s most notable work is probably The Conference of the Birds, a supremely devoted and erudite work of literature about a group of birds representing our human flaws that prevent us from reaching our greatest potential, and our own enlightenment. In Khamenei’s own journals, it was at this point that he began discovering books on his own. He read Attar’s Book of the Divine, and Memorial of the Saints, and kept his personal copies hidden under his straw mattress. When he was nine, he met a girl with violet radiant eyes, and he wrote countless poems that were devoted to her beauty. He filled several journals, and you can read them only if you have professional JSTOR access.

As everyone knows, Khamenei has been a lifelong practitioner of Sufism, devoting the first half of his life to asceticism and the purpose of spiritual transcendence, to commit one’s destiny to what is known as fitra, the Arabic word meaning ‘innate nature,’ the return to tawhid, our oneness with Allah. Sufism is not a religion, it is a mystical practice, a pursuit to purify oneself to the so-called supererogatory level. And Khamenei was no stranger to the more beautiful aspects of his surroundings. As he continued to write, gradually ironing out the clunkiness of his childlike and adolescent prose into a more refined synthesis of man’s relationship to the world around him. In his early adulthood, he would pace around his maturing garden of citrus trees and pansies and primrose and foxgloves, and water them methodically from an aluminum watering can, the kind that rains lightly from a hundred tiny holes. And he would write his sonnets in his head as he did this every morning, just as the sun peaked above the crumpled butcher paper mountains, above the clothesline of drying linens, the shadows spilling forward like crooked jesters. When he returned to his writing desk he would transcribe what was beamed down to him, like he was a vessel, some medium that God channeled his wisdom to:

You are the Essence of the Essence, the intoxication of Love. I long to sing your praises but stand mute with the agony of my wishing heart!

Raise your words, not your voice, it is rain that grows flowers, not thunder.

This is how I would die into the love I have for you: as pieces of cloud dissolve into sunlight.

Of course, this is the more brutish translation of English, our language of stuttering honks, these bucktoothed screeches of despair in comparison to the flowing cursive of its original form, sprawling methodically across the page like tendriled ivies, this benevolent flora of our earthly nirvana. Part of the problem is that our language cannot be entirely trusted. We are devoted to our instinctive state, a kind of shrillness that excels in manipulation, convincing ourselves that we are always right, a language of overindulged confidence. Walt Whitman got closer than anyone, at least closer than any American, as he claimed his poems were more songs than anything else. Translations are hard not only because it is impossible to directly translate word for word, but more so because you are reading a poet’s verse from a culture that could not be more different from your own. Even with our best efforts, it is naturally a translator’s interpretation of the verse, followed by your incredibly abstract understanding of it from your modern Western perspective. If a Sufi poet from the 13th century were able to watch The Sopranos or Sex and the City, dubbed in his own Farsi, he wouldn’t know what in god’s name was happening. Nevertheless, here we are, trying to dissect meaning from the elaborate and the ancient.

Khamenei was on his was to being a Sufi poet. He wrote in his journals how he cared only for the way a winter garden turned into one for the springtime, the special way a tree could look dead for months, with gray-brown sprigs and feeble posture, and it would suddenly bulge with miraculous pink buds at its tips, and leaves would grow out of seemingly nowhere. There was an infinite storehouse of stuff to write more poems from. But as all things in history, the Americans and the British intervened, and they ruined everything.

The thing is, at this point of his youth, Khamenei was a famous Hanafi faqih—he was a jurist within the strict sect of Islamic jurisprudence that devoted itself to a more moral decency, pursuing only the godliest realm that embraced its worship of women to the highest of its capable praise. He wanted to commit his life to restoring the ease and accessibility of his faith to his townspeople.

It was an early morning in 1953 when he knelt down to pray his first prayer of the day, when all hell broke loose. You see, Khamenei was just supposed to be a simple Sufi poet, committed to his praise of women and his love for his garden and the lizards and birds and all creatures around. At the time, the democratically elected Prime Minister of Iran, Mohammed Mosaddegh, wanted to nationalize the Iranian oil supply. Until then, the British Empire was siphoning the vast majority of the oil reserves for its own profit. When the Prime Minister wanted to change that, the U.S. joined the UK in doing what the West knows best: staging a coup d’état, overthrowing the democratically elected leader, and giving the shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, far more control than he had held previously, anointing him an autocratic king (Shah is Persian for king). This is undisputed, as a massive cache of previously classified CIA documents were released in 2013, showing their CIA-MI6 joint operation code-named Operation Ajax (Operation Boot in the UK), including manufactured riots instigated from the cruelest gangsters they could find in Tehran, as well as false flag attacks and black propaganda. The operation killed hundreds, and forever set the stage of the autocratic rule that followed, leading to the 1979 revolution, and the political state that Iran is in today.

Whenever people share photos of Iran from before the revolution, displaying how women walked around freely, in skirts, without the hijab, they do so usually with the intent to show how barbaric Islam is towards women. And they are. The leadership in Iran is famously not friendly to women or to gays. But these things don’t just happen out of nowhere. Throughout our short American history, we have overthrown too many democratically governments because doing so was in our interest at the time, and then when things got bad we blamed them for being the way they are. Aside from the obvious cruelty of overthrowing a government just to take their oil, it’s the shortsightedness that never ceases to amaze. We do thing kind of thing often. A more famous example was when we supported the mujahideen in order to fight back the Soviets, not anticipating the seemingly obvious—that training and arming these strange people of the desert, with that special arcane guerrilla resiliency that these types of people have—would eventually have dire consequences. U.S. interventions contain a kind of lore to them. They are legendary at this point, causing the further unraveling of the world.

I read Timothy Weiner’s history of the CIA, Legacy of Ashes, a little over a decade ago, and remember being aghast at nearly every page, revealing yet another covert operation that went bust, another secret agent that turned against them or went missing or was caught and then killed. You read this book, and not only are you expectedly appalled at the criminal enterprise that the CIA was and is (mostly was, as we can all agree they have kind of lost their luster), but you are also mostly in awe at their sheer incompetence, these god-fearing goons that sold drugs to a cartel in exchange for weapons that they could then sell to some guerrilla army to fight their enemy. And it seemed like they always fucked it up. Legacy of Ashes was published in 2007, six years before these new documents of the CIA’s coup in Iran became public. But the theme remains the same: the Central Intelligence Agency has left the world in a far worse state of instability than the world that existed before. It spreads a legacy of death and misery and an irreparable arrogance that the flexing of intervention works. Because these people began intervening and somehow convinced themselves that it was a good idea to continue what they were doing.

Modern Christianity in America is a godless kind of religion. No American evangelical actually believes in a God like they say they do. There is no judgment, no heaven, no hell. There is no moral point or objective to anything they pretend to be in pursuit of. In a traditional sense, we are all atheists, in that we no longer believe our prayers are being carried like passenger pigeons up to the heavens. Rather, the God the evangelicals worship is a personified form of America, or more likely of capital itself, what is known in the New Testament as mammon, the mad pursuit for material wealth, the temptation that greed is indeed good. This is American Christianity, and largely Christianity as a whole, where capital is the center of its idolatry, and these people are screeching knaves, wild-eyed and paranoid beasts, driving the gears of power because of their terror. They’ll invade a country that they’ve only vaguely heard of, but only partly driven by their hatred of other religions, only partly because of the darker shade of people. Mostly, they’ll start bombing a place because they’re driven by the seething undiagnosed schizophrenia they permanently suffer. What they call Christianity today is now just a synonym for the American Empire.

The gall of the American Empire is one solely for its own ravenous self appeal, its own indulgence and righteousness. Imagine for a moment if a foreign government staged a coup and overthrew your government. Imagine they installed a religious king that stripped everyone’s rights away, and took all the wealth from your own nation’s resources. And then imagine decades later they blamed you for it, they gaslit you beyond your wildest dreams, and then invaded you again because they didn’t like what happened to the mess that they created. This is of course what the U.S. did to Iran.

There was a few hours there, when Donald Trump ordered the bombing of Iran’s nuclear sites, when the fate of the world seemed uncertain. There was a general fear spreading about, people tweeting ravenously about their concerns that WWIII was coming, this sense that things were generally in order for a further unraveling of calamitous events. Maybe Iran would carry out a series of strikes at American bases in Qatar and Bahrain and elsewhere. There are something like 40,000 troops stationed in the Middle East, ready at any time to serve their country for any illogical reason whatsoever. Maybe China or Russia would have finally defended the attacks on Iran. Israel would have dropped a nuclear bomb on Iran, and all the nuclear superpowers would have gotten involved, the orgiastic climax of Dr. Strangelove’s Cold War fantasy, the American cowboys yeehawing their way to a gleeful incineration.

I was spending a couple weeks at a villa in a fairly remote corner of Tuscany, reading and writing by the pool, learning about Renaissance history during the opportune time off. But since I left my home in Los Angeles, American politics have been a committed death drive. It seems like countless things have happened in the short three weeks since my wife and I left: the LA riots against the insane ICE raids happened, protestors burned Waymo’s and pummeled cop cars; a MAGA guy killed a Congresswoman and her husband and tried killing others; Trump had his stupid birthday military parade; Israel killed so many more children, it’s hard to believe there’s still children left for them to kill; the IDF are calling the food lines the Hunger Games because they enjoy killing people scrambling in line for food; and finally, when Israel began bombing Iran out of nowhere, and Trump announced he would make a decision within two weeks as to whether or not the U.S. would get involved. Seymour Hersh reported on his Substack that his sources said Trump would surely get involved and begin bombing. And then just two days after Trump made his two week announcement he launched the B-2 bombers to drop their notorious bunker buster bombs. Iran had to do something in response. Surely they couldn’t just bend over and take it like they have in the past. So they bombed the American base in Qatar. For a few uneasy moments it seemed like it was possibly headed for something we all feared. I should have known. But there’s a general you should keep in mind: if everyone on the internet is screaming that we’re headed for World War III, that probably means nothing is going to happen. My friend sent me a screenshot from the NYT app update, where the reporter Farnaz Fassihi wrote the update: Three Iranian officials familiar with the plans said that Iran gave advanced notice to Qatari officials that attacks were coming, as a way to minimize casualties. The officials Iran needed to symbolically strike back at the U.S. but at the same time carry it out in a way that allowed all sides an exit ramp; they described it as a similar strategy to 2020 when Iran gave Iraq heads up before firing ballistic missiles [at] an American base in Iraq following the assassination of its top general.

All in all, the amount of restraint that Iran has repeatedly shown over the years deserves some kind of award. Give them the Nobel. They deserve it at this point.

One of the despairs of all this is that of course you can’t applaud Iran. Our binary world of thinking with ones and zeros dominating the consciousness wants to determine one side as the good guys and the other as they bad. Iran has funded terror states; they’ve hung women for being raped; they’ve thrown men they accuse of being gay off buildings; and they’ve generally made the world a less righteous and peaceful place. But this is political speak. If you come out and speak on the conflict, you have to condemn Iran in some fashion so as to not get blamed for supporting these things. You have to say yeah Iran is bad, but look at the scale of these other things that Israel is guilty of. The only difference this time is that we created the conditions that we are now fighting against.

You may have seen the Ayatollah’s tweets from around 2014. They resurfaced after Israel began bombing Iran, and people presumably began to dig through his Twitter history to find out what the man casually opined about. They went viral for a moment. People were amused that this religious codger who was going to return some exchanges that would lead to WWIII had such innocent and rather naive musings about the world. He wrote about beauty, and love, and playful memories from his youth. Some of them are as follows:

U can’t leave all tasks 2ur #wife&then criticize her.Even if she’s a scientist/politician,yet when interacting within family,she’s a #flower

Looks like a lot of women are going as beautiful for Halloween

Man has a responsibility to understand #woman’s needs and feelings and must be neglectful toward her #emotional state

I went 2school w/a cloak since1st days;it was uncomfortable 2wear it in front f other kids,but I tried 2make up 4it by being naught&playful

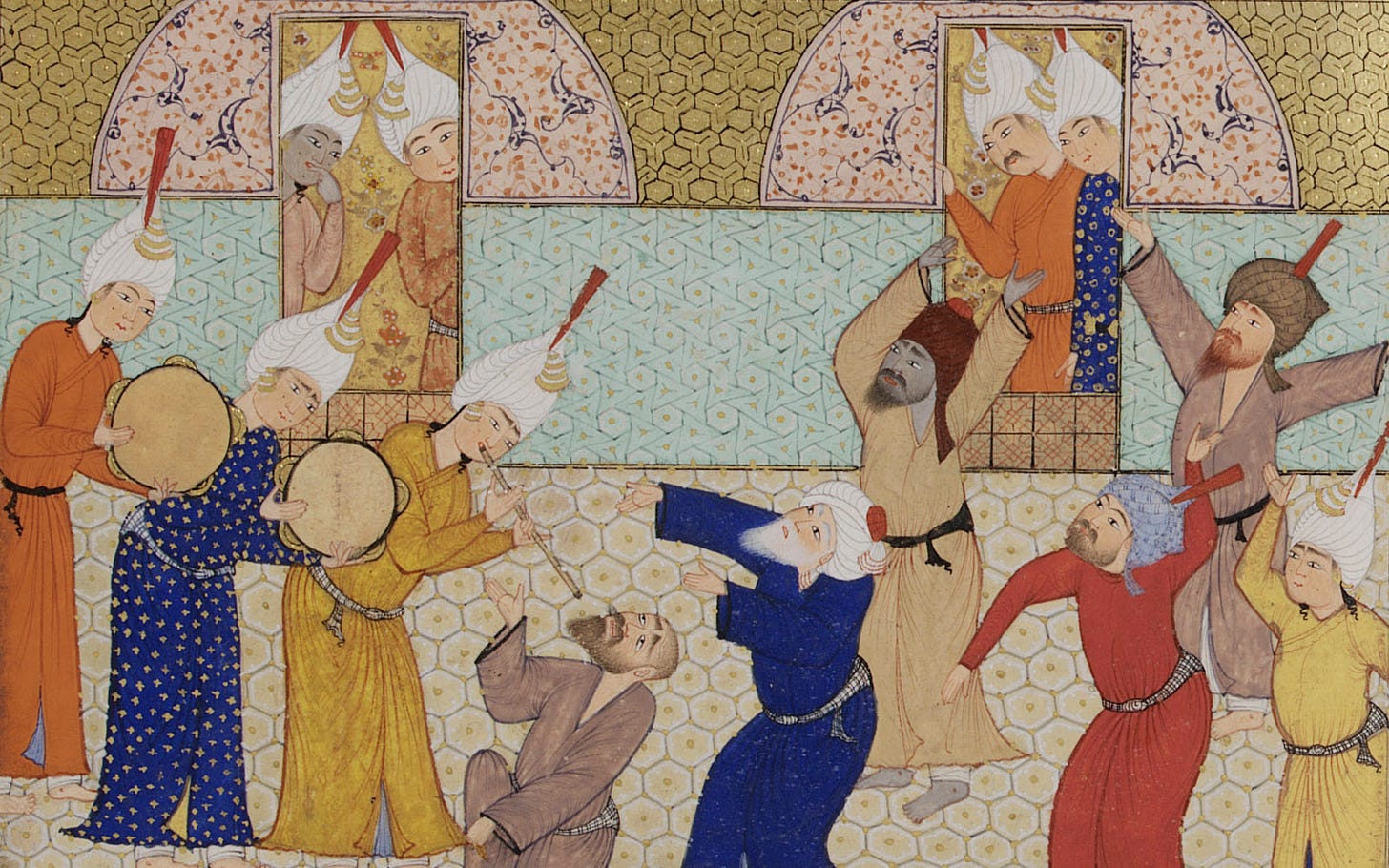

There are many of these. And while it garnered some amusing attention amid the frantic and abundant terror that people were screeching about, it paints a more interesting picture than it lets on at first. Perhaps you realized that the Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the Supreme Leader of Iran, is in fact not a Sufi poet. The childhood that I described at the beginning of this essay was more in line with the famous 13th century poet Rumi, and the verses I shared were also from him. But consider for a moment, that this fate were actually possible if it weren’t for our constant interventions. Consider for a moment that Khamenei was never meant to lead Iran towards religious zealotry, but instead he was destined for his cute musings about innocent love and memories from his childhood. I think the same is true for Trump. He was meant to just stay on Twitter as an entertainer, ranting about Kristen Stewart and Robert Pattinson. This is where he shined. But he was forced to be a politician because of the current conditions, because the working middle class has been dumped, and he was the best charismatic orator who channeled some mutant anger that gave voice to the bovine combover people, the freaks who see empathy as a weakness, the Christian addicts. I have always said the Trump is spiritually gay. Somewhere in there, in the back of the beast’s psyche, he has drag queen energy. He should have been allowed to nurture that side, and become a raging lipsticked queen with a garish bird nest pompadour, who would from time to time kill another queen backstage. He was robbed of this fate, and instead chose politics partly because it chose him. Similarly, the Ayatollah Ali Khamenei should have been a Sufi poet. He should have joined the whirling dervishes, and twirled and twirled, and thought about the beauty of the flowers under moonlight. Let the man write.

Always such an incredibly interesting take with immense research behind it.